This week Senate lawmakers called for total defense spending in fiscal 2018, which begins Oct. 1, of $700 billion. A total of $696.5 billion was proposed by the House committee Monday, which was approved by the House Appropriations Committee Thursday.

The Senate committee’s summary of the bill stated that it backed a $640 billion base budget for the Defense Department and the national security programs of the Energy Department. The bill would also authorized $60 billion for Overseas Contingency Operations to fund operations in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan.

The House committee’s summary of the bill stated that it backed a defense budget of $631.5 billion with an additional $65 billion to fund current wars in the Overseas Contingency Operations account.

The actual defense budget cap imposed by the Budget Control Act (BCA) for 2018 is $549 billion. The BCA of 2011 was signed into law five years ago on Aug. 2, 2011. The BCA reinstates budget caps for a 10-year period ending in fiscal year 2021 with separate caps for the defense and nondefense parts of the discretionary budget.

The House and Senate will need to make a final decision on the defense budget before the September deadline to avoid a sequestration, which last took place in 2013. This isn’t the only way officials are looking at cuts to the armed forces. In 2016, Pentagon officials released a reportto Congress on the need for another Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC). The report stated that the Army’s excess capacity is 33 percent, the Air Force’s is 32 percent, the Defense Logistics Agency’s is 12 percent and the Navy’s is 7 percent.

The House and Senate will need to make a final decision on the defense budget before the September deadline to avoid a sequestration, which last took place in 2013. This isn’t the only way officials are looking at cuts to the armed forces. In 2016, Pentagon officials released a reportto Congress on the need for another Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC). The report stated that the Army’s excess capacity is 33 percent, the Air Force’s is 32 percent, the Defense Logistics Agency’s is 12 percent and the Navy’s is 7 percent.

President Donald Trump’s Pentagon spending plan for 2018, sent to lawmakers in May, included a new round of BRAC. The proposal, which is part of Trump’s Pentagon budget of $639.1 billion, has asked Congress to approve a BRAC in 2021. Similar requests sought in recent Pentagon budgets proposed by former President Barack Obama’s administration failed to gain any traction, due to opposition of BRAC and its potential effect on communities that surround military bases. The Department of Defense sent legislative proposals for the 2018 defense authorization bill to Congress last week. In the package was a more than 60 page request outlining how a new round of BRAC would work.

Pentagon budget documents state the Defense Department holds about 20 percent more infrastructure than is necessary to operate effectively. A BRAC round, which is now barred by law, could potentially save $2 billion annually for the Defense Department, according to Pentagon estimates. Congress rejected two Pentagon requests for restarting the BRAC process in 2012 and 2013 and further barred the military from even planning for future BRACs.

The last BRAC, initiated in 2005, was the largest and costliest, resulting in the closure of about two dozen major military installations across the United States and the restructuring of dozens more. Other BRAC rounds occurred in 1988, 1991, 1993 and 1995. Pentagon officials have said the savings since the 2005 BRAC have exceeded upfront costs associated with the closures and realignments. It was estimated to cost $21 billion. It reached $35 billion. If a 2021 BRAC is approved, who will be on the chopping block?

During BRAC rounds 2-5, some of the military installations in Texas that closed included Bergstrom Air Force Base in Austin, Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Dallas Naval Air Station in Dallas, Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio, Lone Star Army Ammunition Plant in Texarkana, Red River Army Depot in Texarkana, Reese Air Force Base in Lubbock, Naval Station Ingleside in Ingleside, Brooks City Air Force Base in San Antonio and Chase Field Naval Air Station in Beeville.

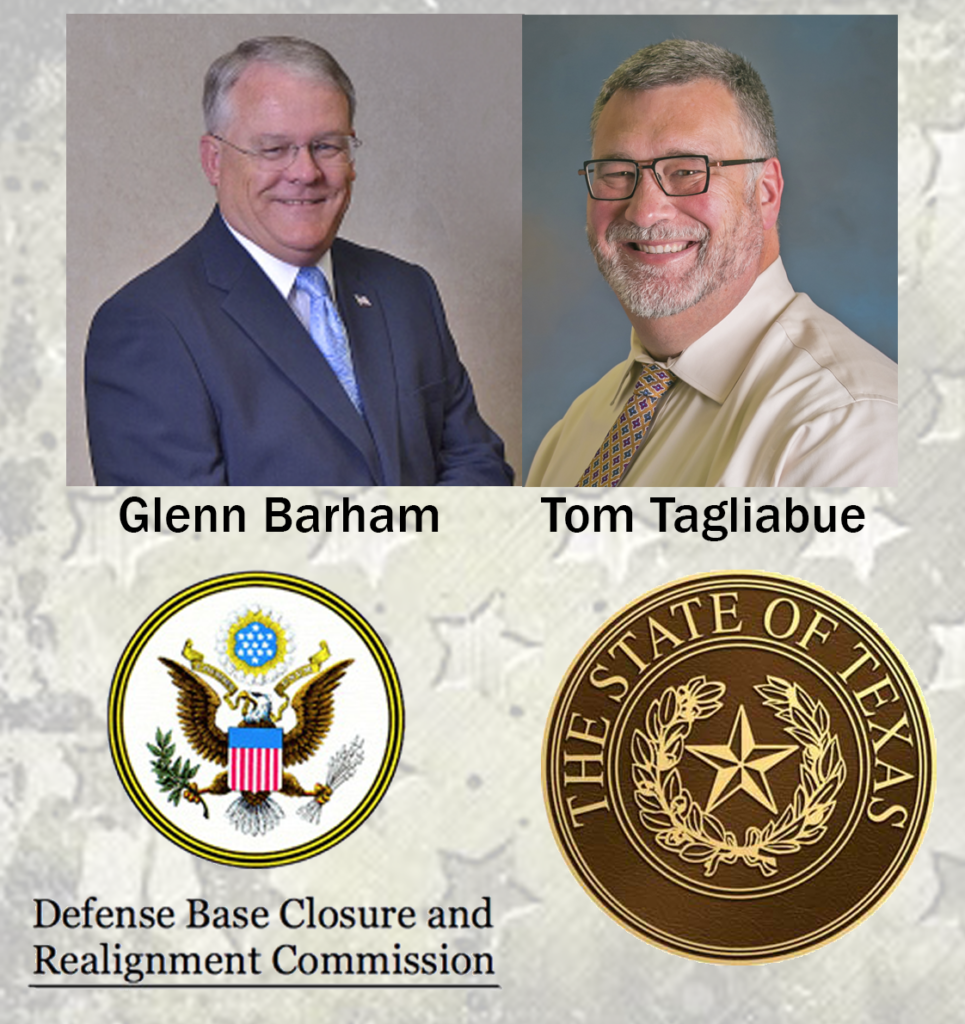

Some Texas installations downsized or grew as they took in those who left closed installations. “In 2005, Sheppard Air Force Base housed what I think was the largest basic medical training wing in the Air Force,” said Glenn Barham, former Wichita Falls mayor and president of the Sheppard Military Affairs Committee. “The BRAC commission recommended that all medical training wings throughout the military be consolidated to one base. The result of that was Sheppard lost the wing and it was moved to San Antonio along with other medical training. The impact to the economy in Wichita Falls was the loss of about 2,000 jobs and $48 million to the area economy.”

In a 2015 study on the economic impact of military bases, the office of Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar stated that the 15 major military installations located in Texas generate more than $136.6 billion in economic activity each year. They also generate $48.1 billion in annual personal income and support, directly and indirectly, nearly 806,000 Texas jobs.

Corpus Christi Intergovernmental Relations Director Tom Tagliabue said that the city has a vested interest in protecting and enhancing Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, the Corpus Christi Army Depot, Coast Guard Sector Corpus Christi and Naval Air Station Kingsville. Since BRAC 2005, Naval Station Ingleside had been gradually closing this base. All ships were moved to new duty stations by the end of 2009. When the Navy vacated this 500 acre facility in April 2010, more than 4,000 jobs were lost. The property reverted back to the port of Corpus Christi in May 2010. The port has been actively redeveloping the site focusing on the growth of a ship repair and service facility and a research and development facility, with the assistance of Texas A&M University.

During the 85th Legislative Session, a couple of bills were proposed that could have an impact on potential BRAC status for installations. Barham referred to Senate Bill 277 along with its companion House Bill 445. “They were written to protect military installations with a fixed-wing flying mission from encroachment by wind farm projects,” said Barham. “The House bill did not make it out of the Calendars Committee and died as a result. However, SB 277 was passed by the Senate and sent to the House for consideration. The Senate version of the bill was passed by the House on the last day of the session.” The bill essentially tells a wind farm developer that if they are approved to build a wind farm inside a 25-mile radius of the installation, they will not be eligible for State of Texas tax incentives. The bill does not deny construction of the development. “The bill only denies State of Texas tax incentives,” said Barham. “With the passage of this bill, those military installations with a fixed-wing mission are now somewhat protected from a future BRAC. I only wish Texas could have taken the same approach as Oklahoma. When confronted with wind farm encroachments near military installations was beginning to be problematic, Oklahoma passed legislation that stopped all State of Oklahoma tax incentives on any wind farm development thus protecting military installations in Oklahoma.”

As many as nine Texas military installations could be protected from unfettered wind farm encroachment – Dyess Air Force Base in Abilene, Laughlin Air Force Base in Del Rio, Naval Air Stations Corpus Christi and Kingsville, Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, Joint Base San Antonio (Randolph Air Force Base), and Naval Air Station Fort Worth Joint Reserve Base.

Senate Bill 715, authored by Sen. Donna Campbell, called for property owners to vote before they could be annexed by a city. This bill did not make it to Gov. Greg Abbott’s desk, but a request has been made to include it in the upcoming special session. Those who support annexation reform, say they want the right to vote when cities decide to annex their neighborhoods. While proponents say annexation is a handy tool for city planners, many have said they’re open to granting voting rights to individuals whose property might be annexed. But concerns over development encroaching on military bases have created a barrier for related legislation.

According to Tagliabue, the city of Corpus Christi supports Rep. Roland Gutierrez’s amendment to SB 715. The amendment would have allowed residents who live near a military base to vote on proposed annexations as long as their neighborhoods could be subject to certain military-recommended regulations. “City council member Paulette Guajardo testified before the House Committee on Defense and Veterans Affairs last week in San Antonio,” said Tagliabue. “I lobbied on behalf of Rep. Gutierrez’s amendment during the regular session. Those pushing hard to keep their area installations off the BRAC list would prefer SB 715 stay out of the special session.”

This is what Guajardo said in her testimony to the House Committee on Defense and Veterans Affairs in San Antonio:

“Annexation is an essential tool for defense communities to prevent incompatible encroachment, whether it be from wind farm developments or commercial and residential development. In 2014 the city annexed 16-square miles of Chapman Ranch where a wind farm company was proposing a project. The company agreed to push its project further away. Just a few months ago, the project’s new owners reached an agreement with the city on a de-annexation plan to protect that 16-square mile area for the next 25 years. In the upcoming special session, if an annexation bill is considered – which the city continues to oppose on principle – we do support inclusion of Chairman Gutierrez’s language allowing a defense community to apply land use regulations in the five-mile extraterritorial jurisdiction of the city.”

Another bill, House Bill 890, will go into effect Sept. 1. It creates a seller’s disclosure notice for real estate transactions of properties in close proximity to military installations. The bill requires the cities and counties with a military installation within its jurisdictional boundaries to coordinate with the military installation to make appropriate Air Installation Compatible Use Zone Studies or Joint Land Use Studies available on their respective public websites. The seller’s disclosure notice must include a link to the websites.

The signing of Senate Bill 1 was also well received since it appropriated $20 million for the Defense Economic Adjustment Assistance Grant (DEAAG) program in the Governor’s Military Preparedness Commission.

The Department of Defense sent legislative proposals for the 2018 defense authorization bill to Congress last week. In the package was a more than 60 page request outlining how a new round of BRAC would work. The Department of Defense comptroller will evaluate the plans and the need for closures.

The Pentagon will decide what installations will be closed based on mission requirements, the effect on readiness and the condition of the land. Other things taken into consideration are the ability of the installation to accommodate contingency, surge or mobilization requirements and the cost of operations and manpower. A commission would convene in 2021 to decide what installations should be closed and then the President would review and approve the closures.